Search Results

Crowdsourcing Story Maps and Privacy

As we have pointed out in this blog, we have had the capability to create story maps (multimedia-rich, live web maps) for a few years now, and we have also had the capability to collect data via crowdsourcing and citizen science methods using a variety of methods. But now the capability exists for both to be used at the same time–one way is with the new crowdsourcing story map app from Esri.

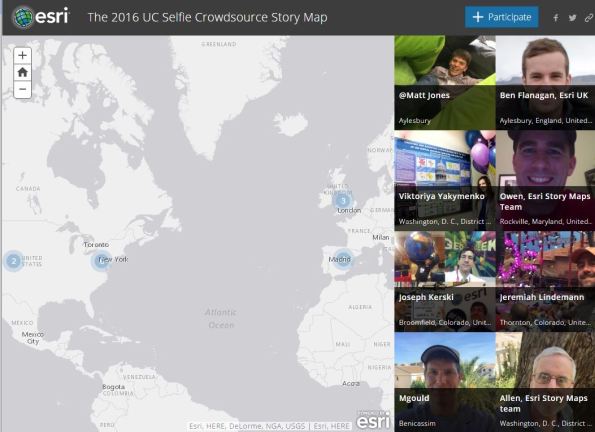

The crowdsource story map app joins the other story map apps that are listed here. To get familiar with this new app, read this explanation. Also, you might explore a new crowdsourced story map that, after selecting “+ Participate”, prompts you for your location, photograph, and a sentence or two about attending, in this case, the Esri User Conference. If you did not attend, examining the application will give you a good sense for what this new app can do.

It’s not just this story map that has me interested. It is that this long-awaited capability is now at our fingertips, where you can, with this same app, create crowdsourced story maps for gathering data on such things as tree cover, historic buildings, noisy places, litter, weird architecture, or something else, on your campus or in your community. It is in beta, but feel free to give this crowdsourcing story map app a try.

We have also discussed location privacy concerns both here and in our book. The story Map Crowdsource app is different from the other Story Maps apps in that it enables people to post pictures and information onto your map without logging in to your ArcGIS Online organization. Thus, the author does not have complete control over what content appears in a Crowdsource story. Furthermore, the contributor’s current location, such as their current street address or locations they have visited, can be exposed in a Crowdsource app and appear with their post in these maps as a point location and as text. This may be fine if your map is collecting contributions about water quality, invasive plant species, or interesting places to visit in a city, where these location are public places. But it may not be desirable for other subject matter or scenarios, especially if people may be posting from their own residence.

Thus, it is up to you as the author of a Story Map Crowdsource app to ensure that your application complies with the privacy and data collection policies and standards of your organization, your community, and your intended audience. You might wish to set up a limited pilot or internal test of any Story Map Crowdsource project before deploying and promoting it publicly in order to review if it meets those requirements. And for you as a user of these maps, make sure that you are aware that you are potentially exposing the location of your residence or workplace, and make adjustments accordingly (generalizing your location to somewhere else in your city, for example) if exposing these locations are of concern to you).

Thus, the new crowdsource story map app is an excellent example of both citizen science and location privacy.

Example of the new crowdsourcing story map app.

Georeferencer Project: Crowdsourcing location data for historic maps

In 2011 the British Library set up the Georeferencer project to crowdsource the georeferencing of its collections of scanned historic maps. By adding georeference (coordinate) data to the old maps, they can be viewed alongside modern maps via the Old Maps Online data portal and the catalog of georeferenced maps.

Using illustrations extracted from digital books and public domain images posted on Flickr, many of the maps were identified and geo-tagged by a team of volunteers as part of a Maps Tag-a-thon event that ran from Nov 2014 to January this year. Among the collections of maps released so far are the Ordnance Surveyors’ Drawings (one inch to a mile maps for England and Wales 1780 – 1840) and the Amercian Civil War collection.

To date, over 8000 maps have been successfully georeferenced and quality checked by a panel of reviewers.

Crowdsourcing Phenology: Marsham’s Indications of Spring

Although there is perhaps a tendency to think that crowdsourcing data collection initiatives are a recent innovation, the practice of citizen science dates back to some of the earliest known recordings of natural and human-made phenomena. In a recent report by the BBC on the signs of spring ‘shifting’ in trees, the pioneering crowdsourcing work of English naturalist Robert Marsham, best known for his Indications of Spring, was acknowledged. Marsham’s interest was in what became known as phenology, the study of the periodic cycles of natural phenomena. His indications of those cycles, 27 altogether, included recordings of the first leafing of a number of trees such as elm, rowan, and oak, the first hearing of birds such as the cuckoo, swallow and nightingale, and the first croaks of certain amphibians. Marsham’s family continued with his observations after his death in 1797, providing almost 200 years of seasonal observations.

Today the same phenological surveys are supported through the Woodland Trust’s Nature’s Calendar survey, a resource for volunteers to record the signs of the changing seasons where they live. A number of live tracking maps are available, which allow visitors to the site to select a species, a year, a particular event such as a first flowering, and plot the results. I chose snowdrops, one of the signature flowers of spring in many parts of Europe. As of the 25 February there had been 487 recorded sightings of snowdrops this year.

Although the spatial data are not available to download, summaries of the seasonal results are available as PDFs.

Geo-Wiki.org: Crowdsourcing to improve global land cover data

In our book The GIS Guide to Public Domain Data, we spend quite a bit of time discussing crowdsourcing, and rightly so: Over the past few years, crowdsourcing has become a viable way not only to collect data, but also to verify and update existing data. Reasons include budget constraints in those agencies that provide data and the subsequent need for field verification, a growing recognition that decisions based on spatial data are only as beneficial as the accuracy of the data sets themselves, the rapid expansion of citizen science, and growth in the number and variety of mobile and web-GIS tools that enable citizen scientists to contribute to the global community.

Examples of verifying and updating existing data are numerous, and a noteworthy one is from a group of researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Austria who lead an effort to improve global land cover/land use data. This effort, http://www.geo-wiki.org, verifies three land cover data sets, including GlobCover from the ESA, MODIS from NASA, and GLC 2000 from the IES Global Environment Monitoring Unit, through knowledge and photographs from people local to specific areas.

Besides an improvement of the data and, it is hoped, in the decisions based on those data, some of these efforts feature innovative projects that provide benefit to local people. For example, Geo-Wiki users were asked to identify the presence of cultivated land and settlements in samples in Ethiopia in a “hackathon” associated with USAID in an effort to improve local food security.

More information can be found on the Geo-Wiki site and in an article describing the project.

Is Everyone a Geographer? Data users as data producers

I have written an essay entitled “Is Everyone a Geographer?”

https://community.esri.com/t5/education-blog/is-everyone-a-geographer/ba-p/892500

In addition, my colleague Barbaree Duke and I included this topic in our recent article, Geography in Everyday Life, in Directions Magazine, here:

I pose this question to the readers of this Spatial Reserves blog because it has direct ties to our book “The GIS Guide to Public Domain Data.” In the Public Domain Data book, we discuss the implications that crowdsourcing has had on the availability, formats, timeliness, and quality of spatial data, and the fundamental shifts it has caused in organizations and for individual GIS data users. Nowadays, everyone is a potential spatial data user, which is quite different from the world of even a few years ago. But even more of a radical shift is that nowadays, everyone is a potential data producer, as well. Whereas in the not too distant past, international and national agencies such as the USGS, UNEP, Ordnance Survey, local governments and authorities, universities, and non-government organizations were the only data producers, now, anyone with a smartphone can contribute data to the GIS cloud and share it so that others can use it. We are only just beginning to grapple with the effects this has had and will increasingly have on the world of GIS.

The book, pictured below, Practicing Geography, is, as the title suggests, stories about people making a positive difference in our world in their everyday jobs. These careers are interesting, diverse, and really show how geography can be applied to practical everyday decision making. I contributed a chapter with several colleagues of mine that shows how students can be engagingly taught about geography careers. The book also illustrates this notion of geography in our everyday lives, as exemplified by the career pathways described in the book.

We look forward to hearing your thoughts about this subject.

–Joseph Kerski

A book review of The GIS Management Handbook, 3rd Edition

At a recent statewide GIS conference in Kentucky, I had the pleasure of meeting Peter Croswell, the President of Croswell-Schulte IT Consultants. Peter is also the author of The GIS Management Handbook, now in its 3rd Edition, published by Kessey Dewitt Publications. The book can be obtained here from URISA, and from the author’s consultancy, here. A review appeared in ArcUser not long ago, here.

As the book touches on many topics that are central to the interests of the Spatial Reserves data blog and our book, I asked Peter if I could review his book to share with our readers; he graciously agreed and my comments and his comments are below. I look forward to hearing your reactions!

From Peter:

When I began preparation of the first version of The GIS Management Handbook in 2008, I thought it would be a relatively straightforward and not too time-consuming effort relying largely on my 25+ years in GIS program and project management. It turned into much more than that—involving substantial literature research and contributions from many GIS professionals. In the two editions that followed, the most recent one being the 3rd Edition (2022), it is an up-to-date, comprehensive, and practical guide to planning, implementing, and managing GIS programs and projects. My goal has also been to provide a useful resource to professionals, academicians, and students. With the release of the Spanish version of the book last year, the audience has expanded quite a bit to readers in Spain and Latin America.

From Joseph:

The book’s central topics of how to develop, implement, and operate GIS projects from a management and program perspective are closely aligned to the themes of this blog because data acquisition, hosting, serving, and use are an important part of any GIS management, whether in government, nonprofit, academia, or private industry organization. In particular, Chapter 5 about funding and budgeting, and Chapter 6, about copyright, public information access, and related matters, are particularly relevant to data and its implications. The book’s chapters on database design (Chapter 7), and GIS projects and management (Chapter 9) also provide not only fundamental concepts, but practical, useful advice from someone who has spent his entire career in geospatial technologies.

Right away in chapter 1 (section, 1.5.5), the author jumps right in to the data topic with a practical discussion of standards and open systems affecting GIS, continuing in chapter 2 with the GIS Capability Maturity Model and the central role that data maintenance and sharing has. Data has a key role also in documenting requirements (Chapter 2), where Peter describes data types and formats, and in database design (also Chapter 2). National spatial data infrastructures, ethics, the GIS data product and service market, how to serve data, fee vs free (Chapter 5), data license agreements, open records laws, crowdsourcing (Chapter 6), data quality management and data sources (Chapter 7), and other topics we regularly discuss in this blog can be more fully understood by reading Peter’s book.

What I most like about Peter’s book is the literally thousands of examples that he provides across a wide variety of topics, so that the book is very practical in its focus. Croswell also provides extensive references and organizations with which to investigate further for best practices. The length and scope of this book are comprehensive but Peter has risen to the challenge of keeping it up to date, relevant, and extremely useful. As such, it provides an excellent supplement to our own GIS and Public Domain Data book and I highly recommend it.

—Joseph Kerski

Societal Implications of Crowdsource Reporting: A Smoking Case Study

A recent report about a mapping and crowdsourcing tool being used effectively in supporting smoke and tobacco free policies on college campuses (https://www.news-medical.net/news/20211021/New-online-tool-effective-in-supporting-smoke-and-tobacco-free-policies-on-college-campuses.aspx) (and published in October 2021 in the Oxford University Press journal Nicotine & Tobacco Research) is a fascinating use of geotechnologies to influence behavior. At the same time, it raises some privacy and ethics concerns. In this case, Survey123 and ArcGIS was used to create a Tobacco Tracker tool, and the effort resulted in over 1,000 people participating in the study. The above report stated, “While (Smoke and Tobacco Free) STF policies are necessary to reduce tobacco-related problems, they are not sufficient without effective enforcement. Reliance on social enforcement by most colleges makes increasing campus-level engagement with these policies a critical, unmet need to accelerate the impact of tobacco control policy.” I salute the innovative researcher involved in this effort and the positive impact it has had. This type of collection and reporting touches on the evolution of volunteered geographic information / crowdsourcing using mapping applications and field data collection tools that goes back nearly a decade now, as we have reported numerous times in this blog. The combination of these tools has led to a plethora of amazing applications such as this one. And one key attraction that drew most of us into the field of geotechnologies is the potential of geotechnologies to enable positive change on our planet, and in our communities.

However, with this or any similar project where people are asked to report on behaviors or activities using these tools, the following questions should be asked:

- What type of data is recorded?

- Are the participants being asked to include people’s photos? If so, are the participants required to obtain permission from the people they are photographing?

- Is the name of the submitter of the data point being asked, and/or the name of the person they are reporting on?

- Who sees the data?

- Is the map is for the project administrators or researchers only, or for the general public?

- If the map and data are shared, many ways exist to avoid sharing exact locations, such as interpolated surfaces or density maps. Are such techniques being used?

- How is the data being used?

- Is it being used to make informed decisions, or to punish?

- If the project is being used to influence a policy, location can be a valuable tool to make decisions. If it is being used to punish, it can be an invasion of privacy.

To be honest, I like it when I am on work travel and am visiting smoke-free campuses. I have also created many videos where I have in dismay stood by piles of litter over the years on other GIS education work trips. I also would rejoice if everyone would follow the rules about littering, smoking, traffic, and other everyday rules. But the idea of people taking photos of other people engaged in specific behavior that we may not like, and then reporting on it makes me uncomfortable, however noble the cause. Is my discomfort warranted? What are your thoughts?

—Joseph Kerski

Reflections on recent GeoEthics webinar discussions

The GeoEthics webinar series from the American Association of Geographers and the University of California Santa Barbara, with support from Esri shares many common themes with this Spatial Reserves book and blog. These include surveillance (including location privacy), and governance (including regulation, data ownership, open data, and open software). I encourage you to watch the archives, including ethical spatial analytics (Feb 2021), responsible use of spatial data (May 2021), and others, and to keep tabs on the page to possibly watch an upcoming webinar live. Webinars are free and open to anyone, and AAG membership is not required, but you need to register ahead of time to watch them live.

On the webinar focusing on ethical spatial analysis, Dr Rogerson discussed examples pointing to instances where spatial dependence may confound the results of statistical testing. These practices raise significant ethical issues for public policy. Dr Vadjunec touched on an issue that we raised in this Spatial Reserves essay: Potential harm from location-tagged data and crowdsourcing. She also touched on privacy, the quality of data provided by volunteers and citizen scientists, issues raised by ethnographic research on very small numbers of human subjects, and the broader issues of trusting representations of the world as big data that may or may not be truthful when compared with real conditions on the ground. Dr Alvarez and Dr Bennett discussed maps as social constructs, how remotely sensed images are processed, and other pertinent related topics. Dr Sieber, in her discussion about artificial intelligence, discussed doorbell cameras, facial recognition, and other topics that will only become more important as time passes, and for which communities, including law enforcement, will have to make some important decisions on how, when, and why to use these tools.

Dr Goodchild, who has for myself and I suspect for many of us been someone we’ve admired and followed for a long time, made comments that made me realize that while we have made great strides in documenting data, we still have a journey ahead of us if we truly want another person or organization to be able to use the data to address a problem with the same workflows and inputs we used, for their own area of the world, or for the same problem with different variables or at a different scale. This is reproducibility. Documenting data is only one part of enabling reproducibility. A key way this can move forward more rapidly is making sure that software companies, including my own, Esri, even more fully document the methods and models that are used for each analytical tool in their toolboxes. This could someday go so far as to send a message to the software user when the user is running an analysis tool, such as the presence of spatial dependence or some other factor. The bottom line is that all stages where spatial data is being processed should be documented and replicable, and efforts need to be made to estimate the uncertainties that are introduced. Accomplishing this rigorously is a noble and difficult to achieve goal.

But part of the responsibility will always be with the data users: Some GIS software such as ArcGIS Pro provide the user with history of the geoprocessing that was done as part of a project (such as a .aprx file). How can we encourage data users to include this history when they share their results with others? How can we encourage software developers to improve tools that will make data sources and methods easily discernible and transparent?

–Joseph Kerski

Coupling data with scholarly research

How many times have you read an article or report and wish you had access to the data that the author used? You’re not alone: A growing concern is being voiced in the research community that data are typically not included with scholarly papers. Why should all this matter? Hasn’t this been the way publishing has always been? Well, in today’s world where serious issues are growing, as recent global health and natural hazards challenges have made starkly clear, the provision of data could provide an immense leap forward for researchers and developers to provide solutions to solving these pressing issues. As we have written about for nearly a decade in this blog, despite crowdsourcing, the Internet of Things, sensors on, above, and below ground, and GIS, statistical, field, and other tools, the task of gathering data, not just spatial data, but any data, still is often a very time consuming endeavor. Research results are important, but should every researcher have to start completely over and gather his or her own data? What if I wanted to take someone’s data and add to it, or use it in another way, in another region, with different models?

Chapter 2 in Open Science by Design: Realizing a Vision for 21st Century Research from the National Academies of Sciences lists several benefits of including data in research studies. The chapter frames these benefits as part of the emerging “open science movement”. The benefits listed by the authors include rigor and reliability, ability to address new questions, faster and more inclusive dissemination of knowledge, broader participation in research, effective use of resources, improved performance of research tasks, and open publication for public benefit. Yet the chapter also recognizes real challenges, including costs and infrastructure, the structure of scholarly communications oftentimes only being available via subscription, lack of supportive culture, incentives, and training, disciplinary differences, and privacy, security, and proprietary barriers to sharing.

The chapter also states that “the ability to automate the process of searching and analyzing linked articles and data can reveal patterns that would escape human perception, making the process of generating and testing hypotheses faster and more efficient. These tools and services will have maximum impact when used within an open science ecosystem that spans institutional, national, and disciplinary boundaries.” Indeed.

An article in Nature also describes the benefits of providing data, beginning with career benefits but touching on societal benefits. Other articles are appearing. And the National Academies chapter above gives practical recommendations as to how to bring about ‘open science.’ The European Union projects FOSTER Plus and OpenAIRE provide training on open science and open data.

But where are the practical examples? I see the following “papers with code” library as one practical response to these concerns, and I salute these efforts:

https://www.paperswithcode.com/datasets

The above site can be filtered, and does include spatial data that I uncovered during my testing, on water quality and other variables. I hope it is the beginning of many such efforts.

–Joseph Kerski

Earth Surveillance Tech changing everything, including us?

A recent article claiming that new Earth surveillance technology is about to change everything, including us, merits a review because it touches on many themes common to our book and this blog. First, as one of the themes of this blog is to foster a critical view of data, recognizing its utility but also recognizing its limitations, I encourage you as I did to investigate the source of any piece of information you find, in this case, Vice.com, the platform where this article is hosted. Vice content is shown on their website, through their news division, a creative agency called Virtue, and their history from 1994 to today. I was glad to discover that the author of this article, Becky Ferreira, focuses on technology and science.

In this article, Becky begins with the Earthrise photo taken on 24 December 1968 from Apollo 8, which I also have found so intriguing that I included it and its impact in a chapter of its own in my book Interpreting the World as one of the 100 most revolutionary discoveries in geography. Becky then asks how we will deal with the subsequent deluge of information that we have about Planet Earth that began (in some ways) with that day in 1968. The author discusses initiatives that I was not aware of, such as ICARUS, that monitors animal populations from instruments aboard the International Space Station, along with initiatives we have discussed in this blog, such as CIESIN, crowdsourcing such as after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, ethics in geospatial technology, sensitivity regarding locations shown on maps and imagery, crowdsourcing initiatives such as OpenStreetMap, and more recently, dashboards for the COVID-19 outbreak.

The Earth surveillance article I mention above in my view is an interesting summary of some technological and societal aspects of geospatial technology, though I wish it provided a look into the future, perhaps accompanied by interviews with some leaders in the field. Perhaps the author ran out of space for this and so I look forward to future installments. I also was hoping the article would discuss more location privacy issues, as the title indicated. I also am intrigued by the notion of how geospatial technologies are changing us as people, a topic that we will continue in this blog and that I encourage others to explore. And while change-behavior topics such how we navigate with phones vs. paper maps and the spatial cognition part of the brains of London taxi drivers have been interesting in the past, in the future I would like to see analyses examining those initiatives where geotechnology is specifically applied to do something good for people and the planet: Hundreds of such initiatives have existed, from Ushahidi crowdsourcing in Haiti, to OpenStreetMap, to Mapillary’s street views, to monitoring trash or invasive species or water quality. What were the benefits? What were the costs? What difference did these initiatives make?

–Joseph Kerski

Recent Comments