Archive

Pokémon GO, GIS, and Safety

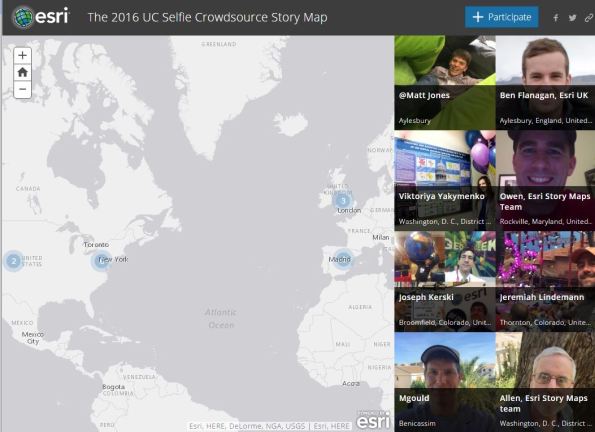

Pokémon GO has become very popular, with tens of millions of users in its first month alone, connecting users in the real world with a virtual world, using their own smartphones. Behind the scenes Pokémon GO is powered by location based services, GIS, and GPS. Pokémon GO is built on Niantic’s Real World Gaming Platform for augmented reality, allowing users to find and catch more than a hundred species of Pokémon as they explore their surroundings. Players are represented on an augmented reality map of the real world. A user’s smartphone vibrates when it is near a Pokémon. When users encounter a Pokémon, they take aim on their smartphone’s touchscreen and throw a Poké Ball to catch it. Finding Pokémon has become much easier with the release of Pokevision, a Pokemon tracker and locator. It uses the Niantic API to grab the location of all Pokemon near you (or your selected location) and displays them on the map in real-time.

This is intriguing to me as a GIS professional for several reasons. First, Pokevision uses map tiles and geocoding services from Esri. It is already the most popular app that uses Esri technology, which makes sense because it is aimed at the general public rather than GIS professionals. Second, the game encourages users to explore the cities and towns where they live to capture. As an outdoor education advocate, I am glad that people are using this game as an excuse to get outside and become active. PokéStops are located at places that I am always encouraging people to visit, such as public art installations, trails, and historical markers and monuments. But I do want people to be safe and be aware of their surroundings whether they are using this game, any other game, their phone, or a GPS. Third, as we discuss frequently in this blog, Pokémon GO is helping people think about the privacy and safety implications of location based services, including games. For example, Chi Smith created a crowdsourcing story map for users to share safety tips. As we discuss in this blog and in our book, location based services are powerful, engaging, and useful, and need to be used with care.

But like all of these technologies and the social forces surrounding them, on 1 August 2016 it was announced that the Pokemon GO developer shut down sites like Pokevision. Keep checking this blog for updates.

POKÉVISION view of the Santa Monica Pier in California.

Crowdsourcing Story Maps and Privacy

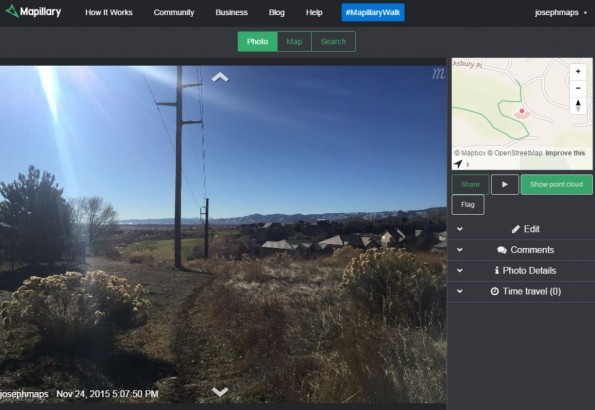

As we have pointed out in this blog, we have had the capability to create story maps (multimedia-rich, live web maps) for a few years now, and we have also had the capability to collect data via crowdsourcing and citizen science methods using a variety of methods. But now the capability exists for both to be used at the same time–one way is with the new crowdsourcing story map app from Esri.

The crowdsource story map app joins the other story map apps that are listed here. To get familiar with this new app, read this explanation. Also, you might explore a new crowdsourced story map that, after selecting “+ Participate”, prompts you for your location, photograph, and a sentence or two about attending, in this case, the Esri User Conference. If you did not attend, examining the application will give you a good sense for what this new app can do.

It’s not just this story map that has me interested. It is that this long-awaited capability is now at our fingertips, where you can, with this same app, create crowdsourced story maps for gathering data on such things as tree cover, historic buildings, noisy places, litter, weird architecture, or something else, on your campus or in your community. It is in beta, but feel free to give this crowdsourcing story map app a try.

We have also discussed location privacy concerns both here and in our book. The story Map Crowdsource app is different from the other Story Maps apps in that it enables people to post pictures and information onto your map without logging in to your ArcGIS Online organization. Thus, the author does not have complete control over what content appears in a Crowdsource story. Furthermore, the contributor’s current location, such as their current street address or locations they have visited, can be exposed in a Crowdsource app and appear with their post in these maps as a point location and as text. This may be fine if your map is collecting contributions about water quality, invasive plant species, or interesting places to visit in a city, where these location are public places. But it may not be desirable for other subject matter or scenarios, especially if people may be posting from their own residence.

Thus, it is up to you as the author of a Story Map Crowdsource app to ensure that your application complies with the privacy and data collection policies and standards of your organization, your community, and your intended audience. You might wish to set up a limited pilot or internal test of any Story Map Crowdsource project before deploying and promoting it publicly in order to review if it meets those requirements. And for you as a user of these maps, make sure that you are aware that you are potentially exposing the location of your residence or workplace, and make adjustments accordingly (generalizing your location to somewhere else in your city, for example) if exposing these locations are of concern to you).

Thus, the new crowdsource story map app is an excellent example of both citizen science and location privacy.

Example of the new crowdsourcing story map app.

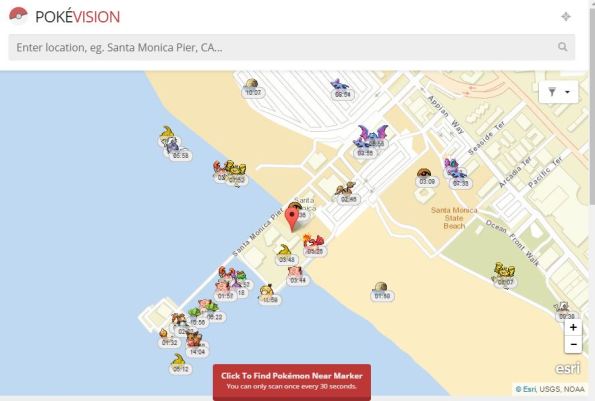

Crowdsourced Street Views with Mapillary

In our book and in this blog, we often focus on crowdsourcing, citizen science, and the Internet of Things. Mapillary, a tool that allows anyone to create their own street level photographs, map them, and share them via web GIS technology, fits under all three of these themes. The idea behind Mapillary is a simple but powerful one: Take photos of a place of interest as you walk, bicycle, or drive using the Mapillary mobile app. Next, upload the photos to Mapillary again using the app. Your photos will be mapped and connected with other Mapillary photos, and combined into street level photo views. Then you can explore your places and those from thousands of other users around the world.

Mapillary is part of the rapidly growing crowdsourcing movement, also known as citizen science, which seeks to generate “volunteered geographic information” content from ordinary citizens. Mapillary forms part of the Internet of Things (IoT) because people are acting as sensors across the global landscape using this technology. Mapillary is more than a set of tools–it is a community, with its own MeetUps and ambassadors. Mapillary is also a new Esri partner, and through an ArcGIS integration, local governments and other organizations can understand their communities in real-time, and “the projects they’re working on that either require a quick turnaround or frequent updates, can be more streamlined.” These include managing inventory and city assets, monitoring repairs, inspecting pavement or sign quality, and assessing sites for new train tracks. One of Mapillary’s goals was to provide street views in places where no Google Street Views exist.

Many organizations are using Mapillary: For example, the Missing Maps Project is a collaboration between the American Red Cross, British Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières-UK (MSF-UK, or Doctors Without Borders-UK), and the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. The project aims to map the most vulnerable places in the developing world so that NGOs and individuals can use the maps and data to better respond to crises affecting these areas.

Using the discovery section on Mapillary, take a tour through the ancient city Teotihuacán in Mexico, Astypalaia, one of the Dodecanese Islands in Greece, Pompeii, or Antarctica. After you create an account and join the Mapillary community, you can access the live web map and click on any of the mapped tracks.

Mapillary can serve as an excellent way to help your students, clients, customers, or colleagues get outside, think spatially, use mobile apps, and use geotechnologies. Why stop at streets? You could map trails, as I have done while hiking or biking, or map rivers and lakes from a kayak or canoe. There is much to be mapped, explored, studied, and enjoyed. If you’d like extra help in mapping your campus, town, or field trip with Mapillary, send an email to Mapillary and let the team know what you have in mind. They can help you get started with ideas and tips (and bike mounts, if you need them).

For about two years, I have been using Mapillary to map trails and streets. I used the Mapillary app on my smartphone, generating photographs and locations as I hiked along. One of the trails that I mapped is shown below and also on the global map that everyone in the Mapillary community can access. I have spoken often with the Mapillary staff and salute their efforts.

We look forward to hearing your reactions and how you use this tool.

Mapillary view of a trail in Colorado USA that I created.

Recent Comments