Archive

Field testing of offsets on interactive web maps

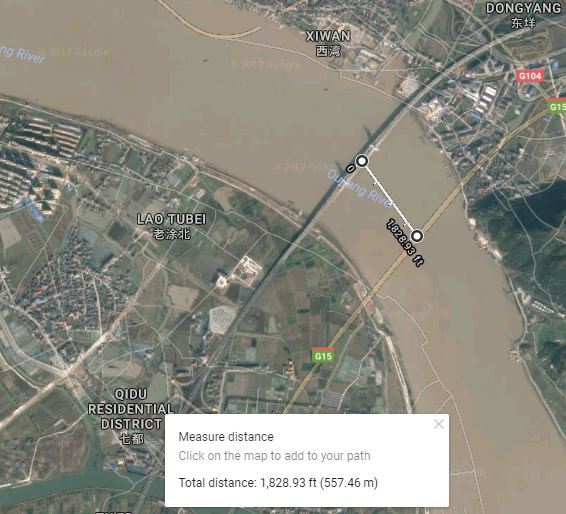

A few years ago we wrote about intentional offsets on interactive web maps. The purpose was to encourage people to think critically about information provided even in commonly used maps such as from Google. Given the interest that this post generated in terms of teaching about data quality, I decided that some field testing would be instructive. Given that the offsets we highlighted in this essay were in China, I enlisted a colleague of mine who is teaching there to take some GPS readings at known-on-the-map locations, to verify the following: Are the vector (streets) data on selected web mapping services offset, is the imagery offset, or are both partially offset and therefore neither is spatially accurate in terms of one’s position on the ground? To recap the situation, see Figure 1 below. The vectors are offset from the imagery by about 557 meters to the southeast.

For the field test, my colleague stood at the intersection of two roads and collected two points, as follows:

Point #1: 32°05’03.89”N, 118°54’54.02”E, or 32.084414, 118.915006

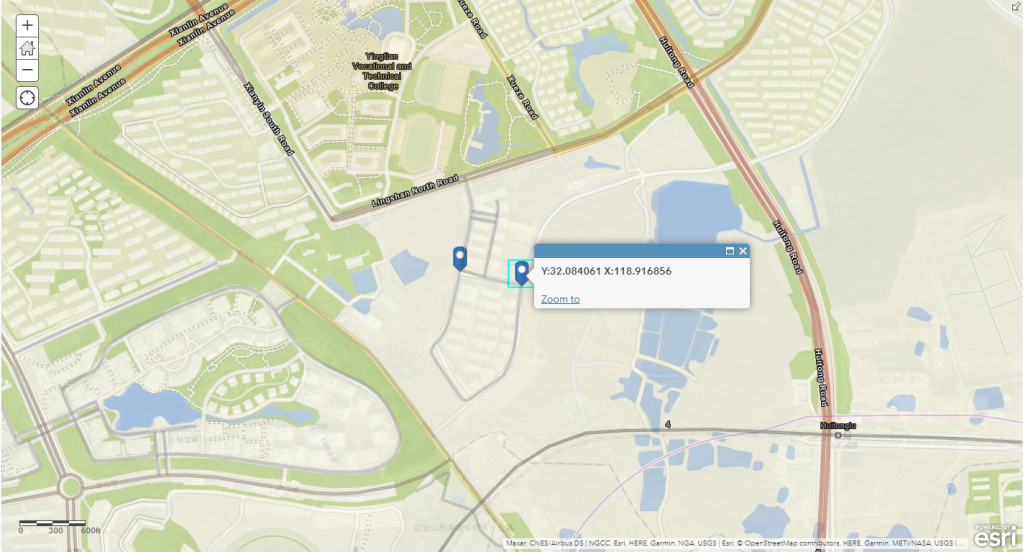

Point #2: 32°05’02.62”N, 118°55’00.68”E, or 32.084061, 118.916856

I first mapped these points in ArcGIS Online. In ArcGIS Online, the two points above aligned well with the default imagery base in ArcGIS Online, with the Open Street Map layer, and with the world streets layer, as shown below and on the map shared here.

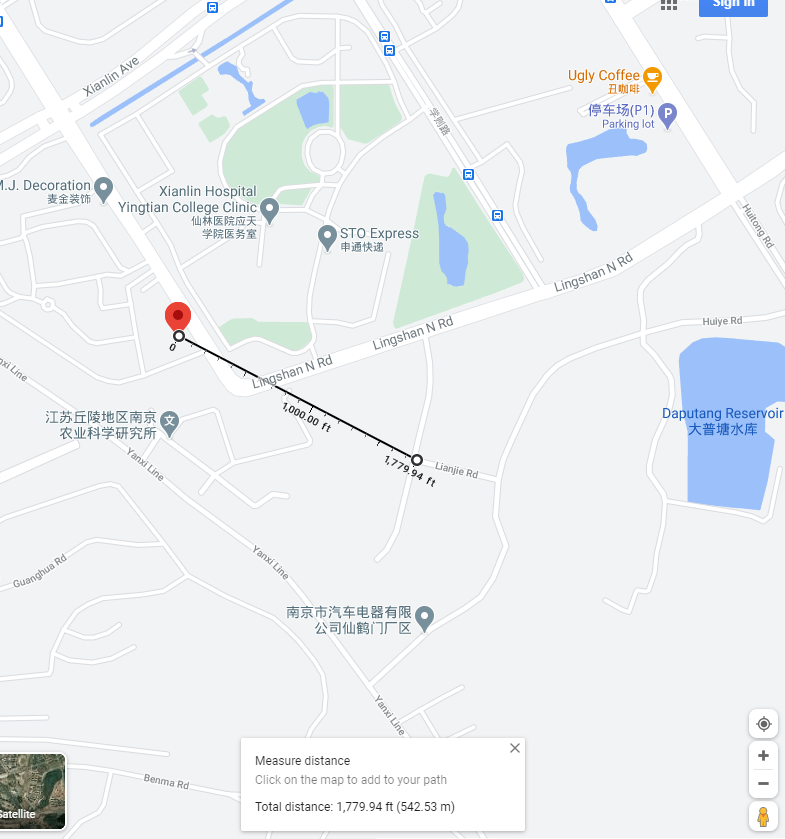

However, when mapped in Google Maps, the following observations were noted: Point 1’s location on the street map is about 1,779.94 feet or 542.53 meters northwest of where my colleague was standing, according to the map.

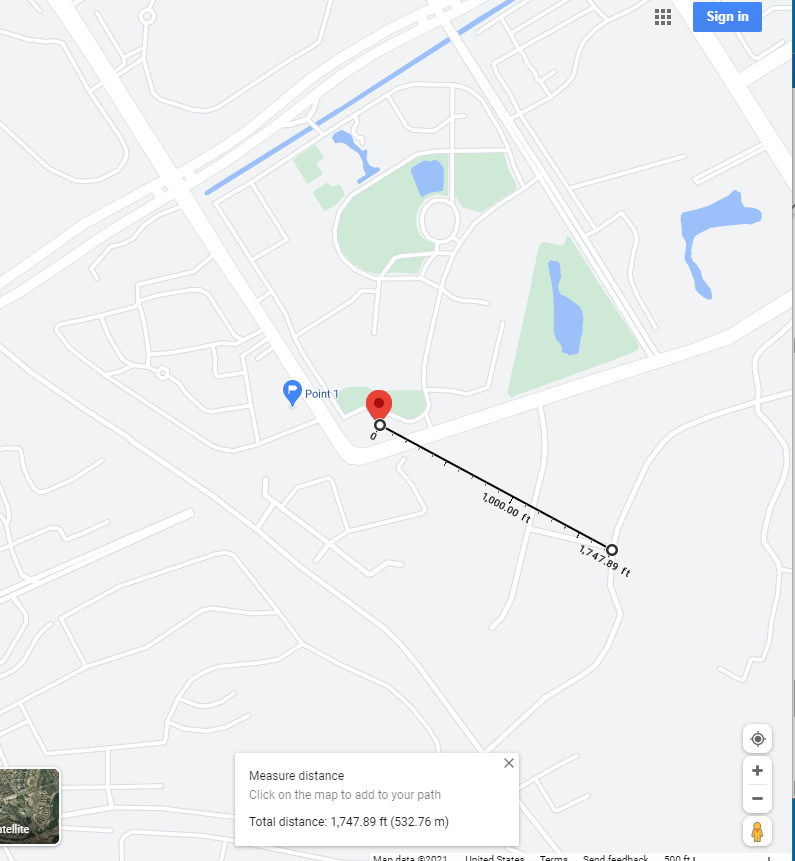

Point 2’s location on the street map is about 1,747.89 feet or 532.76 meters northwest of where my colleague was standing, according to the map.

However, the imagery base map in Google matches well with the actual testing sites. The positions, therefore, are “offset” from the streets layer. I also tested Bing Maps and MapQuest maps; results are below.

Therefore, (1) different streets and imagery layers are either offset or not offset, depending on the layer(s) used; (2) On Google maps, the offset seems to be in this location the same amount (about 532 meters) and in the same direction (northwest) from the imagery to the streets layer, which was the same distance and direction noted a few years ago; (3) these mapping services change over time and are likely to change in the future.

But let’s not be too hasty to assume that the satellite imagery is correct, either. One cannot assume that the satellite images here, or anywhere, are spatially the most accurate layers available. They often are the most spatially accurate, and they are extremely useful to be sure. However, satellite images are processed tiled data sets, and like other data sets, they need to be critically scrutinized as well. First, they should not be considered “reality” despite their appearance of being the “actual” Earth’s surface. They too contain error, may have been taken on different dates or seasons (as we wrote about here), may be reprojected on a different datum; and other issues could also come into play. Second, as you will note just south of the study area, the default satellite imagery is of different dates in ArcGIS Online and Google Maps, with the latter showing (as of the time this essay was being written) a major east-west street being constructed just south of the study area.

Another difference between these maps is a modest amount of variation in the amount of detail in terms of the streets data in China (or anywhere else). The OpenStreetMap is sometimes the most complete, though not always; the other web mapping platforms offered a varying level of detail. The imagery in each platform is compiled and mosaicked from a variety of sources and reflects different dates of acquisition and sometimes different spatial resolution as well.

It all comes back to identifying your end goals in using any sort of GIS. Being critical of the data can and should be part of the decision making process that you use and the choice of tools and maps to use. By the time you read this, the image offset problem may be a thing of the past. But at the time that you are reading this, are there new issues of concern? Data sources, methods, and quality vary considerably among different countries, platforms, and services. Thus, being critical of the data is not just something to practice one time, but rather, fundamental to everyday work with GIS.

We look forward to your comments below.

–Joseph Kerski

Everyday examples of being critical of the data

Each day presents new examples of the central theme of this blog–the importance of being critical of the data, including spatial data. Some of the most effective examples are those rather odd bits of geospatial information, and I have included some of my recent favorites here. These examples are intriguing; some are even fun. They might serve as attention-getting images as you teach students or colleagues about data quality on maps, visualizations, and other forms of communication. If a picture is worth 1,000 words, I say that a map or image is worth 1,000 pictures.

At first glance, from the following result from a phone map search, George Mason University has become a simple Chinese fast-food chain! It begs the question: Is the 4-star rating reflective of the university or of the chicken chow mein?

See this example below from a catalog that I have treasured for a few years. Map orientation matters! This speaks to one of the central goals of my entire career, which is to do all I can to increase geographic literacy. We still have a long way to go! In fairness to this catalog, though, this image has been corrected after I and a few colleagues wrote to them.

Check out the satellite image below. You have heard of life imitating art and vice versa. Is this a case of maps imitating the Earth, or vice versa? I followed the advice we promote in this blog; i.e., I checked several other sources, and it does appear that the pushpin-looking feature in California is legitimate! Notice the dry pushpin-like feature facing the one that contains what appears to be water, and the boat on the desert sands to the southwest of the water feature. The Esri Wayback imagery shows the feature under construction from a image dated February 2014. Still, it is a puzzle what the purpose of a water feature in the middle of the desert is.

“What’s wrong with this picture?” My recent search to fill out a proper bibliographic citation for an article I wrote for the location of the National Academy of Sciences headquarters netted me a location on a house on a cul-de-sac in suburban Denver. How can that be? Could it perhaps be because I was doing the search from a computer in the Denver area?

This errant weather feed below existed online for nearly a year before it was corrected. I know it gets hot in Texas, but really! If the heat doesn’t do you in, the rainfall deluge, impossibly high humidity, and the ferocious winds will!

But even outside of maps, examples are just as numerous. Take a careful look at the Beatles tunes listed below. Funny, I’ve never heard the songs “Penny Lance”, “A Day in the Sky”, or “Can’s Buy Me Love” before! In addition, this isn’t an “album” at all, but rather a user-created playlist but appears on a host of music-related websites.

Feel free to share some additional examples that you have found in the comments section below!

Teaching about spatial data quality

It is important to be critical of data, including, and perhaps especially, spatial data. I frequently receive inquiries from professors seeking resources on the best resources to teach about data quality and foster related discussions with students. Here is one of my recent responses to such an inquiry.

- If you need a fun and engaging set of maps and discussion, use my presentation on Good Maps, Bad Maps, and why it all matters: https://sway.office.com/HqKUCu2ib60rkijh?ref=Link. Scroll down to 30% of the way down in this presentation, in the “Maps Tend to Believed” section. Here you will see a whole set of BAD MAPS. They are misleading, erroneous, or just plain bad for many different reasons – the projection is unsuitable, the data is questionable or impossible (for example, I know it gets hot in Texas but there is a temperature reading from a data feed that is over 3,000 degrees as one example), the legend is misleading, places are blatantly shown in the wrong location, or some other reason.

- A short reading on the above topic, why data quality still matters now more than ever: https://spatialreserves.wordpress.com/2017/12/04/why-data-quality-still-matters-now-more-than-ever/

- More food for thought, presented as the “best available data” “BAD data”: https://spatialreserves.wordpress.com/2017/08/14/best-available-data-bad-data/

- A guide for deciding which data will be useful for your needs: https://spatialreserves.wordpress.com/2018/11/26/a-graphical-aid-in-deciding-whether-geospatial-data-can-be-used/

- An essay reflecting on the 30 checks for data errors: https://spatialreserves.wordpress.com/2015/03/22/gis-gigo-garbage-in-garbage-out-30-checks-for-data-errors/

I hope these resources will be useful to many!

Data quality is a major theme of this blog.

–Joseph Kerski

Be critical of the data even in a time of crisis

The article that recently appeared about the discrepancies in COVID-19 cases and tests fits squarely into the theme of our book and this blog. I invite you to read or skim the article, but just in case the article is no longer available by the time you read this essay, or you would just like a synopsis, it is essentially about this: Some discrepancies about the same data on the same date existed between two data sources. To the readers of this blog and to users of GIS, this is not unexpected: The geospatial data community is trained to examine multiple sources when mapping and making decisions, and collectively, the community has probably encountered this same situation on a weekly if not a daily basis.

Why did the situation in the recent article merit attention? In this case, it was about COVID-19 cases and testing, already a topic intertwined with many emotions, and for good reason. But another reason is that high ranking government officials were quoting one website, Worldometer, and other sources were quoting and using Johns Hopkins University’s site, and others. Why were there differences in the data among the sites?

I have used sites like Worldometer that contain little metadata at times for teaching purposes, but obviously with caution. Worldometer’s population “clock” or “gauge” style of presenting data on world population, for example, makes for compelling teaching, as the population ticks up by several people every second, lending a sense of urgency that can frame discussions about the need for effective planning for agriculture, transportation, water, energy, and other aspects of society. But again, I always use these sites with a wary eye.

The difficulty of discovering how the Worldometer COVID-19 data was derived is the focus of this article. The article’s “sleuthing” style, even going so far to determine the author(s) of the organization behind the data sites, makes for, in my view, interesting and important reading for students or anyone who is working in GIS or data science.

My key takeaways from this story are: (1) As we rely increasingly on real-time and near-real time data feeds, whether about health, or flood stage, or wildfire perimeters, or any other data that is used to make daily decisions, and (2) as the data is increasingly being shared and reported on almost instantly to millions of people, it is more important than ever to understand the source, scale, date, attributes, and other characteristics of the data.

Perhaps the title of this essay needs to be changed from “Be critical of the data even at a time of crisis” to “Be critical of the data especially at a time of crisis”. But I would take it a step farther: “Be critical of the data even when there is no crisis!”

–Joseph Kerski

Creating fake data on web mapping services

Aligned with our theme of this blog of “be critical of the data,” consider the following recent fascinating story: An artist wheeled 99 smartphones around in a wagon to create fake traffic jams on Google Maps. An artist pulled 99 smartphones around Berlin in a little red wagon, in order to track how the phones affected Google Maps’ traffic interface. On each phone, he called up the Google Map interface. As we discuss in our book, traffic and other real-time layers depend in large part on data contributed to by the citizen science network; ordinary people who are contributing data to the cloud, and in this and other cases, not intentionally. Wherever the phones traveled, Google Maps for a while showed a traffic jam, displaying a red line and routing users around the area.

It wasn’t difficult to do, and it shows several things; (1) that the Google Maps traffic layer (in this case) was doing what it was supposed to do, reflecting what it perceived as true local conditions; (2) that it may be sometimes easy to create fake data using web mapping tools; hence, be critical of data, including maps, as we have been stating on this blog for 8 years; (3) the IoT includes people, and at 7.5 billion strong, people have a great influence over the sensor network and the Internet of Things.

The URL of his amusing video showing him toting the red wagon around is here, and the full URL of the story is below:

https://www.businessinsider.com/google-maps-traffic-jam-99-smartphones-wagon-2020-2

I just wonder how he was able to obtain permission from 99 people to use their smartphones. Or did he buy 99 photos on sale somewhere?

–Joseph Kerski

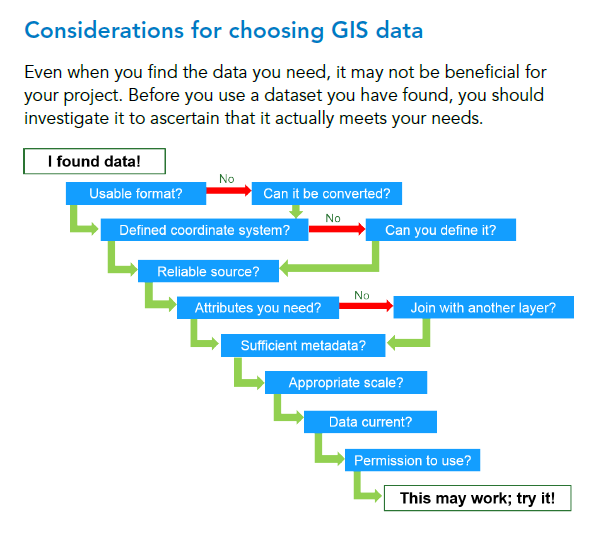

A graphical aid in deciding whether geospatial data meets your needs

The following graphic from an Esri course may be helpful when you are deciding whether or not you should use a specific GIS data set in your analysis. Though simple, it contains several key elements in deciding fitness for use, a key topic in our blog and book, including metadata, scale, and currency.

Another helpful graphic and essay I have found helpful is Nathan Heazlewood’s 30 checks for data errors. Another dated though useful set of text and graphic is from the people at PBCGIS here, where they review the process from abstraction of a situation of a problem, to considering the data model, fitness of data, understanding information needs, and examining the dichotomies of concise vs. confusing, credible vs. unfounded, and useful vs. not useful. PBCGIS created a more detailed and useful set of considerations here. My article published in Directions Magazine about search strategies might also be helpful.

Do you use graphical aids when making decisions about data, or when teaching this topic to others? If so, which are the most useful for you?

Best Available Data: “BAD” Data?

You may have heard the phrase that the “Best Available Data” is sometimes “BAD” Data. Why? As the acronym implies, BAD data is often used “just because it is right at your fingertips,” and is often of lower quality than the data that could be obtained with more time, planning, and effort. We have made the case in our book and in this blog for 5 years now that data quality actually matters, not just as a theoretical concept, but in day to day decision-making. Data quality is particularly important in the field of GIS, where so many decisions are made based on analyzing mapped information.

All of this daily-used information hinges on the quality of the original data. Compounding the issue is that the temptation to settle for the easily obtained grows as the web GIS paradigm, with its ease of use and plethora of data sets, makes it easier and easier to quickly add data layers and be off on your way. To be sure, there are times when the easily obtained is also of acceptable or even high quality. Judging whether it is acceptable depends on the data user and that user’s needs and goals; “fitness for use.”

One intriguing and important resource in determining the quality of your data can be found in The Bad Data Handbook, published by O’Reilly Media, by Q. Ethan McCallum and 18 contributing authors. They wrote about their experiences, their methods and their successes and challenges in dealing with datasets that are “bad” in some key ways. The resulting 19 chapters and 250-ish pages may make you want to put this on your “would love to but don’t have time” pile, but I urge you to consider reading it. The book is written in an engaging manner; many parts are even funny, evident in phrases such as, “When Databases attack” and “Is It Just Me or Does This Data Smell Funny?”

Despite the lively and often humorous approach, there is much practical wisdom here. For example, many of us in the GIS field can relate to being somewhat perfectionist, so the chapter on, “Don’t Let the Perfect be the Enemy of the Good” is quite pertinent. In another example, the authors provide a helpful “Four Cs of Data Quality Analysis.” These include:

1. Complete: Is everything here that’s supposed to be here?

2. Coherent: Does all of the data “add up?”

3. Correct: Are these, in fact, the right values?

4. aCcountable: Can we trace the data?

Unix administrator Sandra Henry-Stocker wrote a review of the book here, An online version of the book is here, from it-ebooks.info, but in keeping with the themes of this blog, you might wish to make sure that it is fair to the author that you read it from this site rather than purchasing the book. I think that purchasing the book would be well worth the investment. Don’t let the 2012 publication date, the fact that it is not GIS-focused per se, and the frequent inclusion of code put you off; this really is essential reading–or at least skimming–for all who are in the field of geotechnology.

Bad Data book by Q. Ethan McCallum and others.

My presentation available online,

My presentation available online,

Recent Comments